| Français | English | Español | Português |

Part One / Rage and Fire 2018

“I stopped in elementary school, but I already knew how to shoot with a Kalashnikov. We were training in the neighborhood.”

A Basra resident, former militiaman

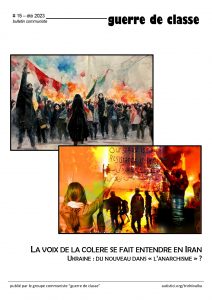

Since the crash of the Islamic State (ISIS) in autumn 2017, Iraqi news has been regularly punctuated by episodes of demonstrations and riots on a background of basic social demands (for access to electricity and drinking water, and for jobs) as well as denunciation of corruption among political staff.

However, this context of peace and finally restored national harmony opened a period particularly favorable to initiate reforms and try to meet the immense social expectations of the population. A precious political capital that the government has squandered in a few months through intense inaction. The anger and frustration of the people are, once again, boundless. The efforts and sacrifices made during the war against the Caliphate were in vain. Over the months, waves of mobilization, violence and the determination of the demonstrators seem to be increasing: riots, fires and clashes with the security forces are increasingly shaking the country. Until October 2019, when the protest movement entered a new phase, on a larger scale, but with different practices. While the government is more than ever in the spotlight, we know however that the State will be preserved.

A country in ruins

War after war, ruins upon ruins. From 2014 to 2017, the northern half of Iraq, with a Sunni majority, is once again ravaged by fighting, first while being rapidly conquered by ISIS (which stops 100 km north of Baghdad), then while being very slowly liberated.

The cost of destruction related to this conflict is estimated by the World Bank at $45.7 billion in January 2018. In some areas, everything is destroyed; cities are almost razed to the ground, in others there is no infrastructure left. For example, only 38 per cent of the country’s schools are still standing, and only half of the hospitals. A city like Mosul was “liberated” from ISIS only at the cost of 8 million tons of rubble and hundreds of thousands of displaced people.

The country’s economy has obviously not been spared, particularly the essential hydrocarbon sector, which accounts for 88% of the country’s budgetary resources, 51% of GDP and 99% of its exports. Nevertheless, Iraq remains the second largest producer of crude oil within the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (Opec), after Saudi Arabia, with an average production of 4.5 million barrels per day. Some infrastructure has suffered particularly, for example the Baiji refinery, the largest in the country, which only partially restarts in spring 2018. For several years Iraq needs to import refined products (including fuel), gas and electricity from neighboring countries, particularly from Iran. Three-quarters of the water infrastructure and half of the power plants are indeed destroyed. According to region, Iraqis receive only five to eight hours of electricity a day, and shortages of drinking water are chronic. In Baghdad, for example, a quarter of the population does not have access to drinking water.

Agricultural production has also fallen, particularly as a result of the destruction of irrigation systems, exacerbating an already endemic rural exodus.

In 2018, the unemployment rate officially stands at 23% in Iraq, but it is estimated to reach 40% among young people (those under 24 representing 60% of the population). In fact, there is relatively little work in Iraq. The first economic sector, oil, ultimately provides few jobs, especially since foreign companies hire many Asian migrants (considered to be more docile and exploited at will than local workers). The private sector remains weak, and in reality there are only two branches of activity that provide jobs for the population: firstly, the civil service, which has five million civil servants (including retirees) compared to half a million in 2003. Secondly, the violence sector, with the Iraqi army comprising approximately 200,000 men, and the Hashd al-Shaabi, popular mobilization units (PMU), around 100,000. The latter, which is a coalition of about fifty mostly Shia militias, recruited a lot in 2014 after the fatwa of Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani ordering the mobilization against ISIS’ troops. Tens of thousands of volunteers (mostly unemployed) responded to this call, one third of them from the province of Basra. Thousands died there, and many returned injured, sometimes amputated. The end of the war against ISIS leads only to a partial demobilization of these troops. A militiaman back in civilian life means for a family one less source of revenue and an extra mouth to feed.

In Kuwait, in February 2018, at a conference on the reconstruction of the country, while the Iraqi government was asking for more than 88 billion dollars, the international community promised it only about 30 billion dollars in credits and investments (in particular Turkey, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Qatar). But, as a result of an exceptional corruption, which is among the strongest in the world, we know that a part of international aid –as well as a part of the oil rent – disappears into the pockets of local politicians. Successive governments have reportedly embezzled nearly 410 billion euros since Saddam Hussein’s fall in 2003, which means twice the country’s GDP.

On top of that, as Iraq at war has become familiar with debt, in 2016 the country signed an agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and, in exchange for loans, it committed itself to taking austerity measures (drop in the number of civil servants, increase in electricity prices, increase in customs taxes and income taxes, etc.).

As we can see, in Iraq, the years of liberation and reconstruction are unlikely to one day be considered glorious. Disappointment, frustration and anger of the inhabitants seem as great as before the Caliphate episode. Either because they certainly get no benefit for it (ruined or displaced veterans or civilians), or because they have once again lost everything (ISIS’ supporters, Sunnis humiliated by the Shia occupation). It seems we are back to the status quo ante. Or worse.

The premises of the revolt (2011-2015)

During the Arab springs of 2011, thousands of Iraqis took to the streets of many cities to express their anger against an (already) corrupt regime and deplorable living conditions. The movement was quickly and violently repressed by Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, at the cost of dozens of people killed. Whereas the security situation seemed at all levels definitively restored, American troops left the country at the end of the year. Subsequently, the Sunni provinces experienced new episodes of protest, and the government’s responses were the same: a policing response. Enough to enhance the breeding ground for the growth of ISIS, and to explain that a part of the population will welcome it in 2014 as a liberator.

Despite the war, popular demonstrations against corruption, supported by part of the Shia clergy, broke out in Baghdad. In July 2015, they were mainly led by supporters of the thundering Muqtada al-Sadr. But in the south of the country, in Basra and Kerbala, it’s mainly the repeated power cuts that bring people onto the streets. To calm things down Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi, who has been in office since 2014, merely promised reforms… that do not come. Iraqis’ anger boiled over once again from February to May 2016. The “Green Zone”, Baghdad’s ultra-secure perimeter hosting official buildings, was even briefly invaded, and the Parliament was occupied by Sadrist demonstrators. In February 2017, another attempt to occupy it ended this time in failure, four dead and dozens wounded. In front of the “Green Zone”, on the opposite bank of the Tigris, Tahrir Square becomes a symbolic place of protest. From now on, usually on Friday after the prayer, we can see handfuls of activists and protesters gathering, waving posters and holding meetings. But the epicenter of the proletarian revolt lies further south.

Venice adrift

The South-East province has a population of about five million, but its capital Basra alone has three to four million inhabitants. In theory, it is one of the wealthiest regions in the country (if not in the world), since nearly 80% of Iraqi oil is extracted from there (more than in neighboring Kuwait). The agglomeration is hosting a significant petrochemical activity and in its suburbs the only Iraqi ports overlooking the Persian Gulf, including the deep-water port of Umm Qasr (50 km further south). It is from this point, completely saturated, that commodities (including foodstuffs) enter Iraq and millions of barrels of oil are exported daily. Many foreign investors are present in the city (e.g. French or Italian shipping companies), and studies for new industrial and logistical infrastructures are not lacking. Nor indeed the pharaonic real estate projects that seem to be the most delirious: construction of five-star hotels, high-end residential units, shopping malls, business district with the world’s tallest tower (230 floors). To rival the likes of Dubai, as some expect. In the meantime, real economic activity brings millions of dollars a day to the Iraqi State, almost nothing to the region, and even less to its people.

The province of Basra has long been a major agricultural area, renowned for its date palm trees. The Shatt al-Arab estuary, which was a treasure of ecology wealth and developed a lush agriculture, has turned into an ecological hell, devastated by decades of war, laying concrete and industrial pollution – with an ad hoc incidence of cancer for its population. But worse, between the rise in sea level due to global warming and the decrease in river flow due to intensive irrigation (construction of dams in Turkey and Iran, wasteful use in Iraq), we are now witnessing an increasing salinization of land and groundwater.

“A few weeds are scattered over the cracked piece of land. ‘In the past, everything was very green here. I used to grow vegetables, fodder for my animals, dates and apples.’ With his four hectares of land, his herd of about thirty sheep and his few cows, this farmer could earn up to 25 million dinars a year (about 20,000 €).‘But this year, I lost everything. Nothing will grow. I have three children to feed, so to survive, I sell my animals.’ Faced with the shortage of fresh water, this 60-year-old man must now fill their drinking troughs with water bottles.”

Recently, the government had to ban crops that consume too much freshwater, such as maize and rice. This contributes, as do the expropriations of peasants for the extension of oil infrastructure, to a major rural exodus that feeds the slums and informal neighborhoods in the suburbs of Basra. The city’s population has increased by more than one million since 2003. The “pace of job creation” didn’t of course follow, and a third of the population now lives below the poverty line, i.e. on less than $2 a day.

The city’s majestic canals, which used to be called “the Venice of the Middle East”, now look like open sewers and floating dumpsites. Its inhabitants have little or no access to basic public services such as running water, electricity or waste management. In an attempt to overcome these problems, the governorate of Basra has directly signed agreements with neighboring countries. Kuwait thus supplies fuel to Iraqi power plants on a daily basis, but it is first of all out of fear of seeing waves of migrants crossing its border. Electricity supply from Iran is subject to risks such as American sanctions or payment difficulties. Saudi Arabia, which wants yet to counter Tehran’s influence, has so far made do with promises.

That does not mean that the inhabitants of Basra are resigned, but it is true that the region retains traces of a tradition of struggle, particularly trade unionist, and that in the past the influence of Marxist political movements was very important there. Iraqi political Shiism assimilated as many of those aspects as possible in the second half of the 20th century (to counter the communist influence), relying in particular on the pro-social justice veneer provided by this religion. An insurrection like in 1991 against Saddam Hussein’s regime remains almost mythical in many memories. The provincial capital is therefore not, understandably, renowned for its social stability, and demonstrations are a part of everyday life there.

The July riots / Electricity

Iraqi news in the summer of 2018 should been dominated by new political developments following the parliamentary elections in May. The result of this election, which saw a record abstention of more than 55%, was only a fragmented Parliament with no clear majority.

The Saairun coalition (literally “Forward” but also known as “Alliance Towards Reforms” or “Marching Towards Reform”), which could be described as populist and nationalist, obtained the highest percentage of the vote. It was an unprecedented alliance of Shia supporters of the sovereignist Muqtada al-Sadr and the modest Iraqi Communist Party (the latter, however, had only 2 deputies out of 54 elected of the coalition).

In the second place there is the Fatah Alliance (Conquest Alliance); Orthodox Shia and politically inspired by the Iranian model. The party it is led by Hadi al-Amiri; political branch of the PMU [Popular Mobilization Units] and it derives its legitimacy from its active participation in the fight against ISIS.

The party of Prime Minister al-Abadi, the Islamic Dawa Party, is only in the third place.

If, a priori, it seems hard to reconcile one political bloc with another, at least two of them must join their forces in order to appoint a Prime Minister and share the power. This is particularly complex since they must respect ethno-confessional quotas in the distribution of posts and, finally, upset neither Tehran nor Washington. It is after a month of spectacular negotiations and reversals that the first step is over: an agreement to form a government has finally been reached between Haider al-Abadi and Muqtada al-Sadr.

But while politicians in the air-conditioned palaces of the “Green Zone” are now feverishly fighting for the allocation of ministries, Basra’s inhabitants are facing the most serious water crisis in Iraq, as well as frightening heat waves. With temperatures above 50°C, fans, air conditioners and refrigerators become more than essential. But for that you need electricity. And now on July 6th, due to unpaid bills, Iran is simply closing several power lines, including the one that supplies Basra. The proletarians, noting that Shia solidarity has limits, are forced to use their age-old, costly and polluting generators. As for the Iraqi authorities, they find no other solution than to ask the inhabitants… to save energy.

Two days later, on Sunday, July 8th, a demonstration of a quite common kind took place on the outskirts of Basra: a few dozen people blocked a road leading to the West Qurna-2 oil field (operated by the Russian company Lukoil) and West Qurna-1 oil field (operated by ExxonMobil), thus preventing employees from accessing the sites. They hoped to get some hires in this way, but the situation had escalated, and a demonstrator was shot dead by the police. At that moment, no one knows that this event will set off the powder keg.

It seems that initially the local tribal sheikhs sought justice and reparation, and then they received support from other tribes. Demonstrations resume the following Tuesday. The next day, protesters attempted to enter oil installations near Basra, they clashed with security forces and set fire to buildings at the site entrance. The tension is such that foreign oil companies are ordering the evacuation of their executives.

Over the next two days, demonstrations took place in several cities in the south of the country (Basra, Nasiriya, Najaf, Samawa and Karbala) and even in Baghdad. In many cases, protesters were trying to block economically strategic roads, linking for instance oil fields, border crossings (to prevent the passage of trucks), airports and the port of Umm Qasr. Official buildings were occupied. In several cities there were clashes with the police and injuries.

On Friday 13th, Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi travelled to Basra, where he met with military, political, tribal and economic leaders and tried to calm the population by announcing (without further explanation) that he would release “the necessary funds” for the city. During the Friday sermon, Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, faithful to his lukewarm balancing, supported the demonstrators, but asked them to avoid disorder and destruction. However, at nightfall, riots broke out in several cities. The protesters, although very respectful of their cleric, chose to ignore his recommendations and, on the contrary, targeted official buildings, offices of political parties and militias (except Sadrist organizations), and sometimes even tried to set them on fire. Fighting with the police raged all night long. Eight demonstrators were killed. Throughout the following week, these demonstrations were repeated and extended to other provinces in the south of the country.

What do these demonstrators want? Above all, water, electricity, better public services and jobs. A 25-year-old man, a graduate of the University of Basra, says: “We want jobs, we want to drink clean water, and electricity. We want to be treated like human beings and not animals.” Another man, a 29-year-old employee, says, “People are hungry and live without water and electricity. Our demands are simple: more jobs, desalination structures and the construction of power plants.” To these basic material demands, the demonstrators add a vague but virulent denunciation of corruption and all those “thieves” who rule the country. Slogans a little more explicitly political also appear, such as “The people want the regime to fall!”

Throughout the week, the anger that is expressed also took on sovereignist tones, and the demonstrators then also shouted out: “Iran out! Free Baghdad!” The Shia parties, which have been in power for years, are indeed associated with Iran and its far-reaching impact on the country. The symbols of the Islamic Republic (very present in the south of the country) served as outlets for the rioters’ rage: for example, banners and panels in tribute to Khomeini (the founder of the Islamic Republic of Iran) were set on fire.

Who are these demonstrators? First of all, they are exclusively men; especially young (sometimes very young), poor proletarians and unemployed, including young graduates (those under 35 representing 70% of the population). Demonstrations are quite spontaneous, they do not respond to the call of any party or trade union, no leader emerges from them. And even if locally rallies can be initiated by militants or tribal sheikhs, they quickly become uncontrollable. At first, the mobilization seems to concern only the Shias (who anyway represent 60% of the population), the regions of the country and the neighborhoods of the capital where they are in the majority. But it soon becomes clear that the mobilization actually goes beyond community divisions, that Sunnis participate in it, and that some mixed regions are in turn affected.

From the beginning, the anger of the demonstrators targeted the political elite and its symbols, and the seats of the authorities such as governorates, town halls or courthouses; the offices of political parties were regularly attacked, ransacked and burned down. These young proletarians use violence quite “naturally”, spontaneously and impulsively. This can easily be explained by the harshness of Iraqi daily life, by the “brutalization” that years of war have caused society to suffer (in the sense of George L. Mosse), but also by a popular culture that trivializes violence. The Iraqi government prefers to denounce the presence of “vandals” infiltrated into the processions. However, this immoderate use of violence seems to be spreading or at least to be accepted by other categories of demonstrators, as the journalist Hélène Sallon points out: “This willingness to violence was later shared by many demonstrators. People who were not necessarily from this angry and very young generation told me: Well yes, because we don’t have any other choice, they don’t listen to us, they only make promises on promises. And so, at some point, yes, why not violence.” How would it be without the constant calls for moderation from political and religious authorities?

The journalist nevertheless notes a weaker mobilization in Baghdad, perhaps because of the impact Muqtada al-Sadr has there on a portion of the proletariat, but undoubtedly also because of a gap between militants and young proletarians who take to the streets: “In Baghdad, we see that this movement too was not a great success, because I have the impression that the protest there is much more politicized, in line with parties, and anyway we have seen in the demonstrations this summer some divergences between these long-time activists, more politicized and more attached to parties, and this new generation that they could not understand and whose intentions they were not sure of. We have seen a greater difficulty in Baghdad for the movement to make a mix, rather than in Basra or Najaf, where socio-economic reasons are shared by all.”

The authorities, overwhelmed, react in urgency and disorder, becoming only gradually aware of the extent of the revolt. For them, it is primarily a matter of limiting the destruction, hence the introduction of a night curfew and the deployment of riot police using tear gas and water cannons. But, quickly, the army must contribute to protection of the oil facilities in which protesters regularly threaten to enter. In order to limit mobilization, the Internet is interrupted several times throughout the country, sometimes for several days; total cuts or, sometimes, only targeting social networks.

Prime Minister al-Abadi publicly adopts a conciliatory position towards the demonstrators, he claimed to have understood their legitimate demands, and he asserts that he wants to protect the right to demonstrate (peacefully). He also pledges to accelerate water and electricity projects in the South; he invites tribal leaders’ delegations to come and meet him, and he announces an immediate allocation of $3 billion for the Basra region. He can hardly count on the support of his ally Muqtada al-Sadr. Although now with one foot in the “Green Zone”, the latter hopes, as usual, surfing the protest without actually calling his supporters to take to the streets. The fearless Shia leader does not hesitate to use the Twitter’s hashtag “the hunger revolution wins”. Cautiously, he asks demonstrators to show restraint and not to attack public buildings. After more than eight days of demonstrations and probably much hesitation, believing that the movement will continue, he calls on his deputies to suspend negotiations on the formation of a new government until the demonstrators’ demands are met.

The day of July 20th appears to be a turning point. It seems that, in front of the police and military forces heavily deployed in the southern provinces and in the capital, the demonstrators avoided confrontation and gather in the main public squares. In Baghdad, several thousand demonstrators were nevertheless trying to approach the “Green Zone”, but the police pushed them back. The demonstrations, which have become much less violent, continue until Sunday 22nd. It is at this moment that the movement ends, after fourteen days of demonstrations throughout the south of the country, including at least eight days of riots. The repression killed 11 people, most of them shot dead. Such mobilization, violence and repression appear to be unprecedented in Iraq.

September riots / Water

One might think that after such uprising the government would be able to enjoy a soothing respite, but that’s not the case. Everything starts again in Basra, this time because of the water. Due to the deplorable health and meteorological conditions, the water distributed by the authorities has proven to be, from August onwards, much more salty and polluted than usual. In a few weeks, its consumption even causes intoxication and hospitalization of more than 30,000 people.

As always, the government responds by going through the motions, imagining that the suspension of the Minister of Electricity and a few officials will be enough to calm the confrontation and will allow the “Green Zone” to resume its picturesque daily course. However, on Sunday, September 2nd, hundreds of demonstrators blocked various strategic points in Basra province. The next day, in Baghdad, the inaugural meeting of the parliament elected in May was held. The alliance between Muqtada al-Sadr and Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi on the one hand, and that of the leader of the pro-Iranian militias, Hadi al-Amiri, and former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki on the other, are tearing each other apart. But they failed to elect a Speaker of the Council of Representatives.

On Tuesday, several thousand people gather in Basra to protest against the authorities’ negligence. The police shot into the air and used tear gas to disperse them, clashes broke out. At the end of the day, six people were killed. There are even more protesters on Wednesday. On Thursday (September 6th), access to the port of Umm Qasr was blocked by demonstrators and, in the evening, in Basra, rioters attacked public buildings and political parties’ headquarters. They even tried to attack the Iranian consulate, but they were repelled by the security forces. Fearing that demonstrations may be triggered after the Friday prayer (which takes place at noon), the authorities deploy numerous police forces to Basra and set up a curfew in the city from 4 p.m. But if during the day protesters try to enter one of the oil sites near the city, and others block Umm Qasr’s access again, it is at nightfall that the situation escalates. Residents gathered on the streets and, in ever-increasing numbers, they quickly attacked government buildings, party and militia premises, the regional governor’s offices and residence, and they burned down everything that might be. What makes a whole lot of noise, including at the international level, is that the Iranian consulate is stormed for the second time and that, this time, it went up in smoke. During the night, three more demonstrators were shot dead by the police.

The following day, Saturday, September 8th, is particularly calm in comparison. The port of Umm Qasr resumes its activities, and the police watch. Some activists claiming to be “organizers” of the protests denounce the destruction of the previous day and announce that they are stopping the movement. The curfew was finally lifted in the evening. It should be noted that, for the first time, the commander of the PMU declares that his troops are ready to deploy in the streets of Basra to ensure security and protect peaceful demonstrators against agents provocateurs.

The government is once again promising to release funds (without giving any amount or timetable), although no one has yet seen the shadow of the $3 billion promised in July. On the same day, Parliament met in an emergency session in order to discuss the crisis in Basra, but part of the assembly, including the Fatah Alliance (political wing of the PMU), called for the resignation of Prime Minister al-Abadi. But, in a dramatic turn of events, this call was echoed by Muqtada al-Sadr, an ally of al-Abadi until then! The sovereignist leader thus suggests an alliance with the pro-Iranian bloc. This turnaround was facilitated by Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani’s highly critical stance towards the Prime Minister. He was finally forced to throw in the towel, and Adel Abdel Mahdi, a former oil minister, was appointed to succeed him (he did not take office until October 25th, 2018). The situation is still somewhat confusing but, while some denounce the recent riots as the result of a plot aimed at countering Iranian influence, it seems paradoxically that the pro-Iranian bloc will be strengthened as a result.

Nothing that a priori could satisfy the protesters, of whom, in less than a week, thirteen were killed and dozens more wounded. Nothing that would indicate an improvement in their material living conditions. However, the demonstrations did not resume, calm returned, and daily life is getting back to normal in Basra and Baghdad. For how long? Everyone is waiting for the next explosion and remains on guard.

But no one’s realized yet that it will take about a year to see the Iraqi proletarians once again taking to the streets, equipped with their incendiary anger.

End of the first part.

Tristan Leoni, November 2019

Source in French: https://ddt21.noblogs.org/?page_id=2517

English translation: Friends of the Class war

Second part / 2019 Political reform or civil war?

After the revolts of October 2018, Iraq experienced twelve months of relative calm. However, basically the economic and social situation remained broadly the same. Iraq didn’t experience a new wave of protests until October 2019, which initially turned out to be very similar to the previous one. What is new, however, is the magnitude and intensity of the mobilization, the level of violence used by the demonstrators and the level of repression. After a break of a few weeks due to a Shiite pilgrimage, the protest, which looked like extinguished, resumed but appeared to be transformed, on both form and content, and both in terms of demands and sociology of the participants. As the weeks passed, and despite the deaths, the fatigue and the phases of retreat, the movement continues in a quasi-routine of demonstrations and riots… but it can’t find a way out. Although the Prime Minister has promised to meet the demands of the protesters, he was forced to throw in the towel at the end of November, plunging Iraq further into uncertainty. At the time of writing, the mobilization continues.

Prime Minister Adil Abdul-Mahdi, who came to power in October 2018, following the proletarian revolt in Basra that had caused the departure of his predecessor, promised to introduce changes and fight corruption. But, as it looks like a habit, he didn’t outline any significant reforms. It is true that political agendas are not dictated by economic and social considerations but, more prosaically, by business and political rivalries. However, the latter are a part of the opposition between Washington and Tehran, which has been particularly strong since May 2018 and the American withdrawal from the agreement on Iranian nuclear power.

1 / From removal to riot (September 29th – October 5th)

There is always a spark for a mobilization to be triggered, a pretext to take to the streets, a step too far that leads to a shift, even if this first cause quickly becomes outdated or even forgotten. At the end of September, Baghdad grappled with student demonstrations, which were rather classically repressed by the government, and the date of Sunday September 29th is considered as the starting point of the movement: several hundred people gathered on that day to protest against the removal of Abdul Wahab al-Saadi that happened two days earlier. This commander of the Iraqi Counter-Terrorism Service, a national hero in the fight against ISIS, is very popular in some parts of the population. For his detractors, he is above all the man of the United States within the military apparatus. The affair caused a very strong mobilization on the internet, notably via Twitter with the hashtag “We are all Abdul Wahab al-Saadi”.

Two days later, demonstrations broke out in several cities across the country. In Baghdad, the meeting point for the protesters is obviously Tahrir Square, in front of the “Green Zone” on the opposite bank of the Tigris River. The removal is long gone, and the participants take up the Iraqi classic slogans for the improvement of basic services, for job creation or against corruption, reminiscent of the revolt of 2018. One demonstrator said: “All we want is to live and nothing else, we want to live just like the rest of the world. We want very basic rights, electricity, water, employment and medicine. We don’t want power, money or property, all we ask for is to live.” [Deutsche Welle] And another added: “I am out of work. I want to get married. I have only 250 dinars (less than a quarter of a dollar) in my pocket, and state officials have millions.” [Dinar Recaps]

As the protesters attempted to cross the Al-Jumariyah bridge, which separates them from the “Green Zone”, they were welcomed by water cannons and tear gas canisters, to which they responded with stones and by constructing barricades of sorts with burning tires and garbage. But the police also used live ammunition; two demonstrators were killed, one in Baghdad and another in Nasiriya, and more than 200 others were injured.

The next day, Wednesday, October 2nd, military and security forces were massively deployed in Baghdad. The main roads were blocked by armored vehicles, concrete blocks and barbed wire. The Internet was cut off throughout the country (except in Kurdistan); the authorities, targeting Facebook, Twitter and WhatsApp, hoped to put a stop to the mobilization.

Demonstrators nevertheless gathered in Tahrir Square and in several provincial towns, including Basra, Najaf, Nasiriya, Wasit and Diwaniyah. In Baghdad, the road leading to the airport (west of the city) was blocked with burning tyres. Clashes erupted in several localities, where buildings symbolizing power as well as the premises of political parties and militias were stormed. At least seven demonstrators were killed.

While denouncing the actions of “rioters” and “infiltrators” [in France they would be called “casseurs”] among peaceful demonstrators, the authorities imposed curfews in several cities. But nothing helped: demonstrations were now daily throughout the south of the country and they turned into riots, usually at nightfall.

In Baghdad, Tahrir Square became in a few days an attachment point from which the demonstrators tried to reach the “Green Zone” by forcing their way onto the bridge over the Tigris River. But the almost 500 meters of the bridge were heavily defended by the police and segmented by several concrete barriers, over which both sides are fighting for control. On the first days, battles sometimes took place around the square, for example on October 3rd in a square 500 meters further north where two armored vehicles [Humvees] of the security forces were set on fire by the rioters, but the violence was thereafter restricted to the bank of the Tigris River. This large-scale mobilization in the very heart of the capital is a new development compared to the events of 2018.

After a few days, the movement takes on an anti-system aspect and there is now, in addition to the demands of a basic economic nature, a very explicit demand for the government to resign. But what political force could pick up the slack and, in the process, satisfy the protesters?

Just as in 2018, the government seems to be overwhelmed by the violence of the uprising and clumsily juggles between carrot and stick. A complete curfew was imposed in Baghdad and in several regions, and civil servants (i.e. the majority of workers) were told to stay off the streets. Despite orders urging to show restraint, members of the security forces frequently use their Kalashnikov to frighten the demonstrators, sometimes also to hit the most determined of them or to get out of complicated situations. Because fighting has been particularly bitter and, as of October 3rd, 31 people have been already killed, including two policemen (which is not a little thing). Two days later, the death toll was already 100 dead and 4,000 wounded. During this period there were many arrests, but the protesters were usually released after a few hours in exchange for signing a promise not to take to the streets again.

On the carrot side, Prime Minister Adel Abdul Mahdi explained to the protesters that their “legitimate demands” have been heard and that they can go home. He announced ambitious social measures including unemployment benefits, the construction of 100,000 housing units and subsidized land distribution, but didn’t set a timetable. He committed to meet with demonstrators to hear their demands and stated that those killed during the demonstrations will be considered as “martyrs”, which means that their families will be eligible for various benefits.

For his part, the very influential Muqtada al-Sadr is hesitating (as always) between praising the order (the power, where he now has a foot inside) and questioning the establishment: he denounced the violence of the security services and called on his supporters to organize peaceful sit-ins. But, on October 4th, another acrobatic U-turn, he is now demanding nothing less than the resignation of the government (which his coalition had however brought to power [see the first part of this article]) and the organization of early elections!

On Sunday the 6th, the mobilization of the police was impressive and that of the protesters very limited. Processions were prevented from reaching Tahrir Square, what led to clashes, particularly in the Sadr City district, where many demonstrators were killed or injured.

The next day, calm returned, the Internet was restored, and the protest ended. The official toll for this week of violence was 157 dead, including 8 police officers, and about 6,000 injured. In addition, 51 public buildings and 8 political party headquarters were burned down. Never seen before. The sudden end of the protests is not in itself unprecedented, as social movements sometimes die in an unexplained way, and commentators then try, in vain, to determine the cause. The Western media have generally not taken an interest in it, but this sudden interruption can be easily explained… by the weight of religion: the celebration of Arba’een, which was to take place this year on October 19th and 20th. This Shiite pilgrimage, part of which is made on foot, attracts millions of believers from all over the world (but mostly Iraqis) going to the holy city of Kerbala. During this period, the south of the country is paralyzed, Shiite towns and villages empty and roads are filled with masses of pilgrims; police and army are massively deployed to ensure security.

But politics is never far away. On October 20th, some pilgrims wave Iraqi flags and chant “Free Baghdad, Corrupt Go Out!” or “No to America! No to Israel! No to Corruption!” Muqtada al-Sadr indeed asked his supporters to give an anti-corruption aspect to this day.

2 / From riot to reform? (October 25th – 27th)

After Arba’een Day, these millions of pilgrims have yet to leave for things getting back to normal. This will not quite be the case. As early as the 21st, Iraqi security forces were beginning to erect fortifications around the “Green Zone”. Indeed, some people have already planned that the “social turmoil new season” [“rentrée sociale”] will begin on Friday October 25th, when leaving the mosques, on the anniversary of the Prime Minister’s inauguration. Calls to demonstrate on that day and meetings were multiplying on social networks at the initiative of civil society activists. Muqtada al-Sadr cautiously informed his supporters that they have “the right to participate” in these gatherings. The deadline given by Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani to the government to respond to the demands of the October demonstrators and to shed light on the violence they have suffered also expired on this date. To make matters worse, the commission charged with investigating these events gave its conclusions a few days earlier and announced the dismissal of some officers. Nothing that can calm a population obsessed by rumors about plots and the presence of snipers. On the contrary. Anger is growing and, in anticipation, many Iraqis were stockpiling food and fuel.

On Friday 25th, in his sermon, the Grand Ayatollah urged the security forces and demonstrators to “show restraint”. In the early afternoon, the mobilization was impressive. Some protesters occupied the rooftops of buildings, which are reported likely to host snipers, including an 18-storey derelict tower overlooking Tahrir Square and the Al-Jumariyah Bridge, known as the Turkish Restaurant.

Demonstrations took place in several cities in the south of the country, including Basra, Wasit, Nasiriya, Najaf, Karbala, Samawah, Amarah and Diwaniyah. Economic demands were still very present there (water, electricity, jobs, health). We noted the remarkable participation, particularly pictured, of some women, including unveiled women, in the midst of thousands of male demonstrators; one of them said: “I want my share of the oil!”

In the capital, protesters approaching the “Green Zone” were repelled. Clashes erupted in many cities. A part of the Basra Governorate building was torched and two police cars suffered the same fate. The Safwan border crossing was blocked and burnt down. The premises of a militia group were attacked with a grenade in Amarah, resulting in two deaths. During the day, at least 27 attacks and burnings of official buildings took place across the country, not counting attacks on party offices or houses of political leaders. The toll of the day is particularly heavy and unprecedented: 63 dead and 2,300 wounded! Most of them were demonstrators shot dead by live ammunition from the security forces or hit by flat trajectory fires of tear gas. Some were reportedly killed by militiamen defending their premises. Several people also died in building fires. Several provinces were under curfew.

In Baghdad, as the confrontation with the police dragged on, rioters ended up erecting tents in Tahrir Square so that they can spend the night there and have not to reclaim the square the next day. Not far away, pick-ups filled with armed men of the Sadrist militia, the Saraya al-Salam (Peace Brigades, ex-Mahdi Army) were deployed to protect the demonstrators. A presence far from reassuring everyone (they withdrew after twenty-four hours).

The next day, demonstrations, riots and attacks on buildings resumed in the southern half of the country; they are now daily. From day to day, the movement spread even to other provinces, hitherto relatively unscathed, where the Shiites are in the minority. There are reports of student demonstrations in cities such as Tikrit (mostly Sunni) or, more symbolically, in Mosul (Kurdistan). While the gatherings were generally peaceful, they frequently turned into riots in the evening. The curfew appeared to be a poor deterrent, with protesters sometimes even waiting for it to start before taking to the streets.

In Baghdad, the demonstrators focused the attention on the bridge that connects Tahrir Square to the “Green Zone”. Armed with stones and, more rarely, with Molotov cocktails, they tried to push back the police. The dead and wounded were numerous.

Sunday October 27th was a turning point in the mobilization. During this new week university and high school students joined the movement, including religious students from the holy city of Najaf. The following day, the teachers’ union called for a national strike lasting several days in solidarity. It was joined by the lawyers’, doctors’, dentists’ and engineers’ unions. In many localities, pickets and sit-ins were set up in front of the entrances to government buildings to obstruct their functioning.

The sociological composition of the movement is therefore changing. We have no longer to deal only with poor young proletarians from deprived suburbs. It is therefore no coincidence that the demands are changing, whereas until now they were above all material and very basic, and in addition there was only a furious hatred of the corrupt. The order of priorities has changed. For the first time, the press echoed testimonies completely at odds with what we have been hearing since 2018, such as that one of this demonstrator in Baghdad: “We have lost our country, we do not want land, electricity or water, we want to be free and we want to overthrow this government.” [France 24] Or this 24-year-old street medic on Tahrir Square: “Our demands are clear: Change the electoral law and hold a new election that allows us to elect the person we want, not a party that makes agreements behind closed doors to decide our future according to their own self-interests.” [The Washington Post]

Demands are confused and various. But, consequently, the most highlighted demands include the resignation of all the people in government, the revision of the electoral law and the Constitution, the end of a system based on ethnicity and confessional identity, the decrease in the number of deputies, early elections, a reduction in the party power, a government of technocrats, a presidential regime, etc.

The impression is henceforth that there are many more demonstrators and that the protest becomes good-natured, almost joyful. Indeed, at the end of October, a slight decrease in violence was perceptible. The official toll at that time was 100 dead and 5,500 injured. In addition, 98 buildings were damaged or burned down. But it was no longer a question of simply expressing rage by burning everything within reach; political reform is now the motto. An issue with regard to which capital can make immediate and low-cost concessions; a comfort issue.

3 / The form of the movement

“Occupy” on the Tigris River

While a few tents were erected in Tahrir Square during the very first days to provide a first-aid post, rest areas or dining spaces, the aim was, behind the lines, to provide logistical support to those in the front line (300 meters further) who were trying to force their way onto the Al-Jumariyah bridge.

Two parallel phenomena gradually emerged: on one hand, the clashes on this bridge decreased in intensity and turned into a “phony war” for protecting, symbolically, the demonstrators gathered in the square. On the other hand, the organization expanded rapidly. Inhabitants and “businesspeople and shop keepers, otherwise ordinary citizens, who cannot join the demonstrations because they are working” were bringing food and water in solidarity. And it became necessary to manage logistics, to organize the preparation and distribution of meals (especially as free food attracts the poorest inhabitants of the capital), as well as equipment (masks, helmets). The Turkish Restaurant became an annex to the square and dormitories were built on some floors. Handymen made the necessary connections to supply the square with water and electricity. The first improvised medical aid stations gave way to an infirmary with volunteer doctors, nurses and pharmacists, then to a real hospital. The tuk-tuks provide transport for the wounded.

Soon, dozens of tents were erected, covering the entire square and overflowing onto the adjacent roads. The square is transformed into a meeting place for activists, unionists, tribal representatives, members of the civil society or the educated middle class, onlookers, etc. There are a multitude of stands where everyone – associations, unions, corporations, artists – express their demands, giving the square the appearance of an anti-globalization camp: a tent becomes a militant library, another a “revolutionary” cinema hall, here one can write proposals for amending the Constitution, there a stand promotes the “made in Iraq” (against products made in Iran), next to a vendor of tricolor flags, a legal office or a stand of the Communist Party of Iraq. For their part, “street artists” decorate the walls with political mural paintings.

As the days passed, the square became a more comfortable living space, restaurants and street vendors are expanding rapidly, hairdressers and barbers set up shop and, of course, prayer rooms are opened. But it is also about keeping busy, because days and nights are long, hence the gigs and chess tournaments. And then there is the sport: runners organized a mini-marathon, volleyball courts and football fields were marked out. On football match nights (as part of the 2022 World Cup qualifiers), a huge crowd are watching the game on a giant screen. And when Iraq won the match, the party went on all night long.

Although a memorial devoted to protesters killed, the atmosphere is festive and good-natured. As in Beirut, the song Baby Shark is on track to becoming the (not very warlike) anthem of the square. This style of camp can be found, on a smaller scale, in other cities, notably in Basra and Nasiriya.

The organization is intended to be beyond reproach because, for some people, it should reflect the image they have of the ideal Iraq… and they evoke “a mini-state” on the square. So groups of volunteers sweep the streets and collect garbage. Hence also the question of security. In the first days, demonstrators set up roadblocks around the square in order to redirect traffic. Then a security service [stewards] was set up for controlling every entrance into the square; people are searched to prevent weapons and dangerous items to be smuggled. If necessary, suspicious individuals are “reported” to the police who patrol the adjacent streets with the agreement of the occupants. The shops (with closed curtains) and warehouses around the square are “secured” by stewards to prevent theft or looting. While many took pride in the fact that women with strollers could safely move around the square, the most determined proletarians were told to get out.

The women

Another significant fact is that since October 27th women who were until then absent from the mobilization have become involved in the demonstrations, although they are still in an extremely small minority. They are most often female university and high school students moving as a group (frequently all-girl groups). Their processions are sometimes protected and supervised by men.

Their presence is most visible of course in the center of the capital, Tahrir Square. But women may be in the majority in the community kitchen, first aid stand and street art: “These women and girls have helped the injured, carried the wounded, provided food and supplies, painted inspiring slogans on walls, washed clothes and cleaned the streets.” While they do more than that, the division of labor and space allocation remains much gendered.

This involvement is a new development in Iraq, where since the 1990s, and especially since 2003 and the growing Islamization of society, the situation of women is getting worse at all levels (social, educational, legal, labor, violence, etc.). Some people consider that the 2019 movement can help to change the “traditional” view held by many Iraqis (and Iraqi women), particularly that one which excludes women from political life. From this point of view, it is noteworthy that women present in Tahrir Square are not victims of widespread sexual harassment or violence (unlike what happened, for example, in 2011 in Cairo’s Tahrir Square).

However, one may wonder what the situation is beyond the center of Baghdad, where activists, students and young people from the middle class are concentrated among others. All the more so, it should be remembered, female participation remains very minority. In the provinces, demonstrations often have an even more male-dominated feature. While some of the country’s major cities have had camps similar to that of Tahrir Square, the southern half of the country is known for its conservatism, and tribal traditions are dominant there, particularly as regards women (need to show humility, arranged marriages, dowry system, honor killings, etc.). Women, especially students, who are going to demonstrate often have to face family pressure (some of them use surgical masks, very common among protesters, to avoid being recognized).

On the other hand, as soon as the situation becomes tenser, as soon as clashes break out, we no longer see any woman in the streets, rioting in Iraq is a man’s affair – it’s obviously not a question of bravery. By the way, more than 99% of the demonstrators killed are men.

Insurgency?

What is striking is the contrast between the festive atmosphere of Tahrir Square, “transformed into a carnival-like hub”, and the harshness of the clashes taking place 500 meters away.

After a few days of occupation, the mass of demonstrators was such that they overflowed the square and gradually took over the bank of the Tigris River upstream of the Al-Jumariyah bridge. Due to the increasing formalism on Tahrir Square, the bridge ceased to be a point through which one tried to reach the “Green Zone”. Henceforth, everyone defended their positions in an impressive confrontation that was like a show (the protesters took possession of a first concrete barrier, and each side stood in a sheltered position). The most radical elements left therefore the square and tried to block or even to cross the three bridges located further north (Al-Sinak, Al-Ahrar and Al-Shuhada). The police forces tried to prevent them from doing so. Many fights took place in Al-Khalani Square and Al-Rasheed Street, strategic places for access to this sector. They were generally very violent; with rioters (very young men) throwing stones (often with slingshots) and Molotov cocktails at the police who responded with tear gas, stones and sometimes Molotov cocktails! The sloppy appearance of the security forces was sometimes such that one had the impression of watching two rival gangs fighting each other armed with sticks. Except that one of them had Kalashnikovs. Under these conditions, a day of rioting without death or serious injuries is a miracle. Several members of the police forces also died in the course of the clashes.

In the capital, however, the confrontation keeps a symbolic and a ritualized aspect. It does not extend beyond the district north of Tahrir Square, there is no destruction, almost no looting, and no attempts to spread the conflict to other parts of the city (except very occasionally). Moreover, it is clear that, for many, it is not a question of attacking the State and the police forces in general, since police officers are circulating around Tahrir Square and collaborating with the protesters’ security service [stewards] (on December 1st, soldiers and demonstrators cleaned up Al-Rasheed Street together). In the capital, the police strategy seems to be in fact above all defensive – defending the “Green zone” and the strategic routes leading to it. This can be explained particularly by the weakness of the anti-riot forces, which probably do not have the means to recapture Tahrir Square. Such a recapture would require the army or the PMU and would provoke a bloodbath with uncertain political consequences. In provincial towns, this ritualized aspect of violence seems much less present, and material destruction is commonplace.

Late November, after renewed clashes, it seems that the rioters’ actions were more criticized by some of the demonstrators, backed by the media and who inverted the reality by evoking an intrinsically peaceful movement in which outside elements came to advocate violence and sow chaos. We even saw demonstrators interfering between the police and rioters (to hinder the latter’s action).

Blocking the economy?

From the outset of the movement, protesters have targeted economic infrastructure – oil fields, refineries, roads, bridges, border crossings, harbors, airports – which they consider to be of strategic interest. A few dozen or several hundred of them set up roadblocks on the way leading to these sites and, above all, they burn tires to prevent the passage of trucks and employees. There is, of course, no national strategy that have been developed, and the roadblocks are, over the weeks, erected and then removed over and over again depending on the protesters’ mobilization, the repression they suffer or local negotiations that take place between the authorities, tribal sheikhs and potential representatives of the demonstrators (for example, a tribal chief may be promised to recruit about ten people against unblocking a site). The most emblematic case is that of the port of Umm Qasr, near Basra, whose accesses are very regularly blocked. The country’s administrative services are also the target of numerous blockades and sit-ins that paralyze their functioning.

Strike actions seem to concern intermittently only the public sector. The private sector is, as we have seen, relatively underdeveloped [see Part One]. The most strategic sector is the oil sector and, as a result, it’s very likely that workers are treated a little better there than elsewhere. Since oil extraction and export is almost the country’s only source of income, the government’s priority is to ensure its continuation, hence the adequate security deployments. It works since, despite two months of mobilization, the level of oil exports has not been affected by the events. At most there have been reported some disruptions in the flow of crude from some oil fields to Umm Qasr, or a slowdown in activity at refineries (sometimes leading to local fuel shortages), but these impacts are relatively marginal. While it is surprising that this sector is not, one way or another, at the heart of the protests, the situation is still likely to change.

However, blocking the port of Umm Qasr, the main entry point for imports, would cost the Iraqi economy several billion dollars. Dozens of ships were unable to unload their cargo. This is a real problem for the entry of food products (cereals, oil, sugar, etc.) on which Iraq is highly dependent. The price of certain foodstuffs (especially vegetables) has risen sharply in the capital.

Finally, it should be noted that the economic activity of businesses (especially the smallest) is also disrupted by frequent internet blackout.

Against Iran

We have already mentioned in the first part the anti-Iranian, sovereignist and nationalist aspects of the 2018 demonstrations. They are very noticeable also in 2019. In the cities of southern Iraq, demonstrators frequently target the various Iranian consulates in the region (and some of their personnel was evacuated early October). The consulate in Kerbala, for example, was stormed several times, and protesters regularly try to raise there the Iraqi flag. In the streets, they attack portraits of Grand Ayatollah Khomeini or General Qassem Soleimani. In Najaf, they rename Khomeini Street “the October Revolution” Street. Statements by the Iranian Supreme Guide, Ali Khamenei, who describes the demonstrations as the result of an American-Zionist plot, contribute to exacerbating the wrath of Iraqis.

This focus on Iranian control over the country (associated with political corruption) remains very present and even peaked at the end of November, when the demonstrations were severely repressed in Iran. The consulate of the holy city of Najaf was thus burned down twice by rioters.

4 / From the “Green Zone”

From October 25th onwards, the situation is so confused that the political forces representing the Iraqi bourgeoisie hesitate about the measures to be implemented to put an end to the protest.

The security forces are mobilized everywhere, but the government seems to favor above all the use of police units, especially riot police, which are considered to be more reliable and in which many former militiamen of the PMU have been recruited in recent years. In some cases, the army is deployed as reinforcement, including very loyal units such as the Counter-Terrorism Service (which proved to be unsuited). But each time, it means taking the risk of seeing these units perpetrate a massacre or, on the contrary, showing little spirit of fight (on November 5th, rioters captured an armored vehicle at Umm Qasr). In Kerbala, on two occasions, unarmed men in uniform could be seen displaying their support for the demonstrators or marching side by side with them. The government is aware that some units may not be obeying orders of very strong repression.

On the security front, it should be added that, during this period, the Internet access was repeatedly shutdown because, according to the Prime Minister, it was being used to “spread violence and hatred”. These interruptions, lasting a few hours or a few days, are sometimes limited to social networks and messaging applications only – although they are based on a less powerful technology than that used in Iran at the same time, since VPN applications are able to bypass them.

The State’s response must also be political in order to separate the more moderate protesters from the more radical. But the politicians are divided, and the first announcements of a cabinet reshuffle leave the protesters completely cold. On October 26th, Sadrist deputies and those of the Fatah Alliance (the political wing of the PMU) withdrew their support for the government and demanded early parliamentary elections (and one wonders who could benefit from them) and a change in the electoral law and the Constitution. The intervention of Iranian General Qassem Soleimani, who then travelled to the Iraqi capital, was necessary, for the Fatah Alliance to restore its support to the Prime Minister twenty-four hours later.

For his part, Iraqi President Barham Saleh promised a new electoral law and early elections, which the Prime Minister hastened to consider unfeasible. Moreover, there’s no guarantee that the announcement of such an election would be enough to demobilize the population as in France in June 1968.

While a parliamentary committee began to draft amendments to the Constitution, bargaining and negotiations were well underway, and on November 9th we learned that the country’s main political forces had just reached an agreement to keep Prime Minister Adel Abdul Mahdi in office and to put an end to the protest “by all means”. However, a program of reforms, in particular anti-corruption, as well as constitutional amendments is implemented to satisfy the population. This is also the work of General Soleimani, who has even got from Muqtada al-Sadr to stop calling for new elections (an idea that is now supported only by the United States). The announcement of this agreement, whereas the protest movement seems to have come to a standstill, is not enough to break the deadlock.

5 / On the threat of civil war

Despite the victory over the Islamic State, the security situation in Iraq is far from ideal. The last supporters of the Caliphate seem to be more active (perhaps because of the events in Syria and the death of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi). And to this we must add the actions of other small Sunni Islamic guerrilla groups. All of them benefit from the mobilization of security forces against the demonstrators. Not a week goes by without a military patrol being ambushed or mortar shells raining down on an airport, an army base or even the “Green Zone”. There are also activists executed, kidnapped or disappeared, and it is questionable whether it’s not the work of spooks or militiamen. In Basra, for example, on October 3rd, masked men shot dead a well-known activist and his wife at their home. On October 5th, armed and masked men attacked the premises of several television stations in the capital, beating up employees and ransacking the scene. On November 1st, in Nasiriya, a PMU commander was assassinated. On November 15th, explosions wounded and killed several demonstrators in Nasiriya and Baghdad, etc. As for the “unidentified snipers” shooting at both peaceful demonstrators and police officers, they are undoubtedly essentially an urban legend.

The situation is confused, but in fact none of the local political forces have an interest in the outbreak of a civil war. Everyone knows that it can also be unintentionally sparked off. All local stakeholders, as well as Iran, have so far been pressing for the situation not to degenerate, and that’s why the PMU militiamen have been in second line since the beginning of the events. During the first two months of mobilization, armed incidents directly linked to the protest were therefore extremely rare and with little impact.

At the end of November, in parallel to the resurgence of violence (among both rioters and police officers), there were signs of an increase in tension at the security level (in the tribes and the PMU) which did not augur well. As described below, the movement seems to have become bogged down and there seems to be no way out. And even if local activists describe the mobilization as always constant, this is at least doubtful. On the other hand, the number of people killed is certainly increasing. In this context, it would not be surprising if the most determined protesters were planning to go further in their fight against the police forces – we have seen in France, by dint of riots, Yellow vests expressing their desire to “come back next time with a gun”, but in Iraq the proximity with weapons is quite different from that in France. Also at the end of November, it seems that demonstrators used explosive devices, and there are rumors about gunshots being fired against security forces.

6 / Stagnation or recourse to violence? (November 1st – November 29th)

Friday November 1st symbolically concluded the week that saw the protest movement taking on a new face with the trade unions, middle classes and students entering the scene. After the prayer, tens of thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands of Baghdadis flocked to Tahrir Square, probably the largest demonstration in Iraq’s history since 2003. In the evening, violent fighting takes place with the police. On Tahrir Square itself, the situation stabilized and the clashes on the Al-Jumariyah bridge decreased in intensity, they were concentrated henceforth on the three bridges further north. On Monday 4th, in Baghdad and Salhiya, demonstrators tried to approach the radio and television buildings, but they were repelled. There are more new deads in the capital.

At the end of the week, the government realizing the deadlock situation but also the growing participation in the movement of a middle class a priori unfamiliar with physical confrontation, once again relies on a strong enforcement presence. In the evening of Thursday 7th, the protesters’ camps are attacked in Basra and Kerbala, and in many cities the police is on the offensive. There were many casualties and a large number of arrests (there are henceforth 300 dead and more than 15,000 wounded). As the port of Umm Qasr resumed operations, teachers’ unions were calling to return to work, and on Saturday the main political forces announced that they have agreed to keep the Prime Minister in office [see above]. Everyone believed that this is a turning point and that the weekend could cripple the movement.

On Sunday 10th, the week began with demonstrations in several cities, but in the capital the mobilization was much smaller than it used to be. The clashes now were concentrated on Al-Khalani Square that the security forces were trying to seize (this is a strategic point controlling access to bridges in the area). In the evening, in Tahrir Square, as fighting raged nearby, demonstrators released white balloons in the sky as a sign of peace.

In the following days, renewed calls to strike by teachers and students allowed the ranks of protesters to grow. While a Christmas tree decorated with Iraqi flags was erected on Tahrir Square, near Basra, for the umpteenth time, residents blocked the accesses to the port of Umm Qasr, to several oil fields, industrial sites and the city’s international airport.

The clashes around Al-Khalani Square were still particularly violent and several demonstrators have died there. After several nights of fighting, the rioters dismantled the imposing concrete barriers installed by the police, regained control of the square and part of the Al-Sinak bridge, and seized an imposing multi-storey car park overlooking the entrance to the bridge, which they converted into an observation post and dormitory.

The fourth consecutive week of mobilization began on November 17th with numerous calls for a day of general strike by the Sadrist movement and several trade union organizations, including, perhaps for the first time, a union of oil workers. The call for a strike, however, has a real effect only on the public sector. The day began as usual with various roadblocks and it was marked in Baghdad by clashes around the Al-Ahrar bridge. Paradoxically, the strategic port of Umm Qasr resumed its activities… only to be blocked again the next day. Nevertheless, in the following days, the mobilization declined and the Ministry of the Interior could even on Tuesday announce the end of “the high alert”. Many henceforth believe that the restoration of calm is possible, and on November 20th important tribal chiefs from the south of the country were welcomed by the Prime Minister in order to discuss the demands of the demonstrators. In the evening, the occupants of the Tahrir Square were dancing and playing music… but the battle for control of the bridges was still raging, and the toll of that night of clashes got heavier than “usually” – four rioters were killed and dozens more wounded (at this stage, there have been about 330 dead and 15,000 wounded across the country since the start of the movement).

The following day, eight more demonstrators were killed in Baghdad and clashes broke out in Kerbala. Fighting also took place around the port of Umm Qasr, but protesters who had been occupying the accesses since Monday were driven out. On Tahrir Square, the sheikhs welcomed the day before were booed and, during the night, it is the Tribal Affairs office in Nasiriya that was set on fire by rioters. Fighting resumed with greater force around the bridges of Baghdad, causing about ten more deaths. But, from then on, new hotbeds of riotous violence appeared: Kerbala, but above all Najaf and Nasiriya. For several days, demonstrators have been blocking the main bridges of the latter, which is the fourth largest city in the country and capital of the province of Dhi Qar, the poorest in Iraq.

The last week of November began with roadblocks and demonstrations throughout the country, but clashes were much more intense than in the previous days (13 rioters killed on Sunday). As the days passed, the level of violence increased and the death toll as well.

In Baghdad, the situation around the bridges remained tense. On the 25th, an explosive device was thrown at the police, injuring about ten of them. Two days later in Basra, another explosive device was aimed at a police officer. Still in Basra, although the demonstrators were still mobilized, they removed the roadblocks after negotiations with the authorities. The rest of southern Iraq is in flames: riots in Samawa, police headquarters attacked in Babylon, a bank burned down in Kerbala, etc.

In the holy city of Najaf, while shooting at the police was pointed out, the premises of an Islamist party was torched by demonstrators, and then, on the 27th, it was the turn of (no less than) the Iranian consulate to be engulfed in flames. But it is in Nasiriya that the fighting seemed the fiercest, where rioters set fire to the Governorate building and the home of a member of parliament, which resulted in a high death toll. The Internet has been shut down in the city. On the 28th, security forces, which received military reinforcements from Baghdad, try to clear the bridges over the Euphrates, causing a new massacre. In retaliation, a building of the security forces was set on fire and that of the military command of the province was besieged. The death toll was 46 (33 in Nasiriya, 11 in Najaf and 2 in Baghdad), one of the deadliest days since the start of the movement.

In the evening, tribal fighters armed with Kalashnikovs blocked some accesses to the city in order to prevent the arrival of new police units. Instead, in Najaf PMU militiamen arrived as a backup force, equipped with armored vehicles, in order to “protect religious sanctuaries”. The following days, despite the curfew, the funeral processions gathered thousands of inhabitants. The situation is explosive… and the Prime Minister announced his resignation.

End of the second part.

Tristan Leoni, December 3rd, 2019.

Source in French: https://ddt21.noblogs.org/?page_id=2545

English translation: Friends of the Class War